It seems to be a truth universally acknowledged, that eating well only means eating healthy foods. A quick look a social media feeds confirms this view. On Twitter, #eatwell streams you dozens of food images with comments on how each ingredient will ensure you a long, healthy, and happy life. Instagram has over 5.7M posts with #eatwell, and they also follow the same perspective.

However, eating is more than just ingesting healthy food for the sake of survival. It’s about establishing and acknolwedging relationships that go boynd our immediate reach.

Elitism of Eating Well

In one of my recent re-posts, I argued that eating well has always been a privilege of the elites.

Throughout #foodhistory, #eating #WELL has always been a #priviledge of the #elite https://t.co/F6IE3DesEY pic.twitter.com/YGTO3Kfp85

— Norman Rusin (@normanrusin) August 11, 2020

I still stand by my claim, but I also want to expand my notion of eating well by including an ethical point of view, which also has political consequences affecting our relationships to ourselves, the others, the environment, our past, and our future.

Eating Well and Communities

The apparently simple act of eating places us inside a complex network of relationships, one which often we’re not even aware of and whose political weight we don’t stress enough. It connects us not only to ourselves, but also to other people, companies and corporations, as well as the environment. It also links us to our past, our future, and the politics of our everyday lives.

In his essay “Eating Well: Thinking Ethically About Food,” Roger King argues that “despite the fast food industry – and as a rebuke to its homogenizing impact – many regional eating traditions in the United States still exist” (King, 179). This trend exists not only in the United States but also in Italy, as the funny, 2009 b-movie Focaccia Blues shows.

Inspired by real events, the film tells the story of the bankruptcy of a Mcdonald’s in Altamura, in Southern Italy, which could not compete with the focaccias from a local bakery. The key to the bakery’s success lies not only in the perceived better quality of its products but also in the relationships between the store owner and the city.

Connection to Our Past …

The store owner has developed her relationship with those people through time, by establishing an everyday routine made of chitchat, flavors, smells, looks. Cirasola portrays a space where people reject homogenization at the service of faster and greater productivity. By refusing to eat fast food, they turn down an experience, whose ubiquity and sameness steal away people’s and places’ identities.

In fact, one key element of the local bakery’s success over MacDonald’s was the store’s unique character. Eating in an anonymous, plasticky venue doesn’t fit many people’s personalities, although many of us are forced to choose them. Deciding where we consume foods leads us to think about how the design of those places affect our consumption and how much time and resources we invest in eating well. In other words, how important is it for us to spend time with other people (family, friends, colleagues, or business partners)? How much time are we willing (or able) to dedicate to choosing, picking, preparing, and sharing foods with other people? Of course, different situations demand different choices, but what we decide is also a political matter. For instance, if our job demands us to never have time for a proper meal—as is usually shown in TV series where protagonists are always afflicted with Atlas personality—that is a direct consequence of both our bargaining power and companies’ control over our bodies and time. Eating well then affects the political balance between the elites and the rest of the population.

By sharing foods and experiences not only do we create, mold, and strengthen our bonds with other people and places, but we also establish our belonging to communities and their roots.

Foods’ power in creating influential memories has been recognized by the political elites throughout the world, who used it as a key element to creating “traditions” and a sense of belonging to newly developed national “imagined communities.”

Acknowledged at first by writers, foods connection to memory processes has been revealed by scientists. Proust’s intuition—we associate smells and flavors to memories of people and places—is confirmed by today’s neuroscience research: motivations, emotions, and cognition work together to form memories in our brains (see for instance Gerald Edelman and Giulio Tononi’s The Universe of Consciousness).

I wouldn’t go as far a Ivan Illich in saying that “mankind may wither and disappear because he is deprived of basic structures of language, law, and myth, just as much as he can be smothered by smog” (Illich, 92). But I question what kind of bonds and memories are we going to be able to create in a fast-food-dominated world? What are we willing to give up to be more efficient, more productive? And will that incontrovertibly lead all of us to more prosperity? In other words, thinking about how we eat pushes us to think about how we want to design our society’s political organization.

… and to Our Future

Our choices today will affect both future generations’ needs and their opportunities to meet them. They will also determine “what resources, institutions, technologies, worldviews, ecosystems, and species will be available for future people to use, admire, respect, and desire.” (King, 185)

Countless sci-fi stories have already explored scenarios in which machines break down foods into their nutrients, reproduce their molecular combinations, and spit out pills or powders, which our bodies need to survive. Not only do such images draw a haunting similarity between human bodies and the machines feeding them, but they also conjure up a dystopian, hardly enjoyable future, in which death looks like something to covet rather than push away, like in Richard Fleischer’s 1973 film Soylent Green.

Based on Harry Harrison’s 1966 sci-fi novel Make Room! Make Room!, Soylent Green describes life in an over-populated, polluted New York City in 2022. To overcome too frequent shortages of natural food and clean water, Soylent Industries—which controls 50 percent of the world food supplies—produces and sells artificially produced wafers made from soy, lentils, and ocean plankton. But when even that food doesn’t suffice any more, riots ensue, and the elites resort to violent policing.

Unconcerned about the spooky reality they were conjuring up, Rob Rhinehart, Matt Cauble, John Coogan, and David Renteln developed Soylent, a powdered mix delivering a complete meal. Started in 2013, the Silicon Valley company is successfully growing and merrily developing more products and flavors.

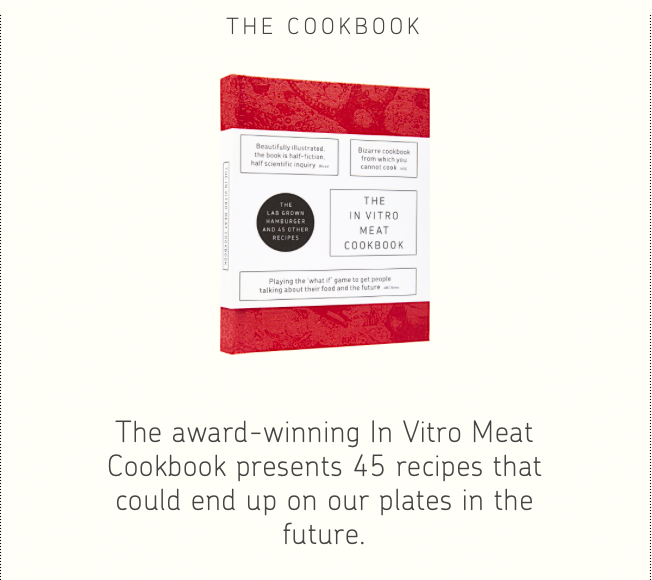

On the other side of the Atlantic—still much attached to their good ‘ol steak—a team of designers, educators, and thinkers came up with The In Vitro Cookbook.

Winner of the Dutch Design Award Research 2014, Next Nature‘s project explores how “in vitro meat, grown from stem cells in a bioreactor, could provide a sustainable and animal-friendly alternative to conventional meat.” Its vivid red illustrations show how “in vitro technology also has the unique potential to bring us new food products, tools and traditions.” This project acknowledges that traditions, as any human product, are created, transformed, and even deleted according to people’s needs. It also makes us question what our relationship to traditions and memories is. In other words, to what extent will it be important for us to remember people, places, and events through food? How will it be possible with lab-created foods?

Such models raise even further questions. How will lab-produced food affect the livelihood and self-determination rights of people whose only source of income depends on those foods grown naturally? Who is going to control technologies, patents, and licensing agreements, in other words, who’s going to be dependent on whom to access key resources? Ultimately, focusing on meeting people’s needs in relation to the design of the food systems’ future means to think about relationships, politics, and power balance between consumers, distributors, manufactures, and producers, all over the world.

Relationship to People and Nature

The political interconnectedness of consumers, distributors, manufacturers, and producers is seldom acknowledged and very often downplayed. For instance, think about how many people still do not believe the current organization of our food system affects climate change, and to what extent that belief informs their eating habits.

Moreover, highly technological food production models don’t take into account nature’s needs. In fact, as we are getting more conscious of how food networks extend beyond our immediate reach, we scrutinize the food industry and its connections to feedlots, mono-crop cultures, and corporate concentration. While sustaining the production of massive quantities of food at ever cheaper rates, these practices annihilate small-scale farmers, depreciate properties around them, and lead to waste, pollution, and loss of biodiversity. Will lab-grown foods avoid, or even help to fix these issues? How?

To better answer these questions, we need to see if lab-grown foods would correct our tendency to conceive of ourselves as being outside of nature. King argues that we look at the so-called natural world “as a storehouse of resources to be used to satisfy human preferences, whether for food or other types of consumption” (King, 184). Molecularized-food production systems will impact our ecosystem, transforming “habitats and environments, but they must do so in ways that preserve the evolutionary integrity of the organisms that constitute them” (King, 182). The answer to sustainability, therefore, is neither purely human-centered nor Earth-centered. But it’ll require us to learn a new way of looking at and conceiving of nature and our role within it.

King urges us to see others in their own terms, as having their own life and purposes and to avoid projecting our own desires, ideas, and agendas on to others (both nature and people). Leaving behind this mono-dimensional way of seeing, he adds, means to acknowledge and feel part of the network of relationships to which eating immediately links us (King, 186).

In conclusion, eating well creates a vast network of relationships and we need to deem ourselves responsible for it. We usually suppose only manufacturers should be held accountable for their actions. However, when it comes to ethics and food, consumption draws all of us into this network of responsibilities (King, 177). People in Altamura pulled off an act of resistance toward a global corporation, perhaps thanks to their strong community bonds and small location. Our consumption habits influence not only our society’s political organization but also the global political network. Therefore, we need to think to what extent these global trends may be (un)desirable and how much power we have to influence their design and development.

Sources

Illich, Ivan. Tools for Conviviality. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1973.

King, Roger J. H. “Eating Well: Thinking Ethically About Food.” Fritz Allhoff and Dave Monroe (eds.). Food and Philosophy. Eat, Drink, and Be Marry. Victoria, Australia: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.